Luke Minford, Rouse CEO reflects on the need for change within the IP industry and how Rouse is leading the way.

The pressure for change

The intellectual property services industry is not adapting fast enough or in a way that meets the needs of the businesses it serves. This puts the industry at risk of major disruption as the gap between what clients demand and what the industry is able to supply widens. And yet, in the face of this threat, the response is weak and incoherent, reflecting a critical lack of urgency and leadership.

Business leaders place ever greater emphasis on the need for diversity of networks and for speed. This is reflected in a growing understanding of how speed and connectedness of decision making impact innovation within the organisation. Leaders like Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, tell employees daily that the most valuable asset they have is their ability to move and connect more quickly than the competition. In order to achieve this they build and connect diverse leadership teams and give them access to ever greater volumes of information and data so that the decisions they take are not just faster, but also more value creating than their competitors. They also embrace open forms of innovation where the collaborative potential of these diverse networks define success. Internally, as new information, technologies, skills, and perspectives emerge, these organisations rapidly adapt and shape their systems, processes and structures in an attempt to out-pace the competition.

In this environment what is the purpose of the intellectual property (IP) services business (IPSB) and how is it adapting to give meaning to that purpose? If we take a broad view, IPSB’s enable enterprises to identify, capture and extract maximum value from investment in innovation. In this sense, and in theory, IPSB’s operate at the heart of change environments, giving life to and sustaining the innovation output of clients. If we take a narrow view of purpose, and one quite often used by lawyers, we would see IPSB’s as organizations that help create and deploy legal assets in order to protect and enhance the competitive position of clients. Whatever view we take, in the context of a rapidly changing environment, how are IPSB’s adjusting their systems and services to match the changing needs of clients? What of the speed and connectivity of their decision making? How are they building and connecting diverse networks of expertise to match the diverse needs of their clients?

Sadly, the answers to these questions are largely negative. The IP industry moves slowly and at a pace that lags behind its clients. It remains fragmented and painfully disconnected as an industry, where lawyers, patent attorneys, trade mark attorneys and other forms of IP specialist battle to define and protect their terrain. For the most part IP is interpreted narrowly within the legal services industry, while the big consultancies and non-law firms who attempt to encroach on IP services remain on the outside, challenged by professional and jurisdictional barriers to entry. As a result, business models and services are not being disrupted fast enough. Attend any major IP conference and you’ll be struck by how little actual change there is within the industry. To some extent that shouldn’t come as a surprise given how complex and internationally connected the IP system has become. Big systems change slowly. It is also partly due to the fact that IP is ‘housed’ within the legal profession, a vocation not known for innovation. This may be because clients employ lawyers to mitigate risk, or it could be down to entrenched and age-old conventions, formalities and hierarchies that operate within the legal system, especially in the West. Whatever the cause for this resistance to change, we are left asking three critical questions: firstly, can change come from within the IP industry fast enough? Secondly, what could that change look like? And, thirdly, when and from where might it arise?

This paper will explore these three important questions.

Organisational life-cycles and the IP industry

“Whenever an individual or a business decides that success has been attained, progress stops.” Thomas Watson, Sr (Founder, IBM) *

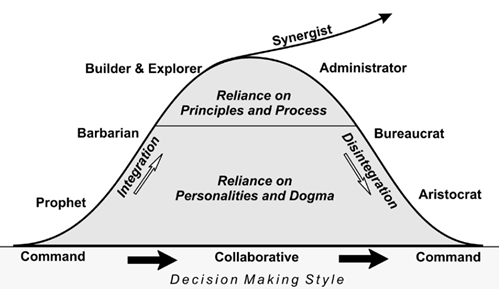

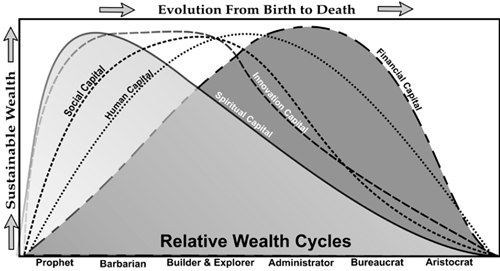

Lawrence M Miller’s* seminal work on organisational life-cycles looks at the characteristics of organisations and their leadership behaviours. He identifies phases in the life-cycle and maps these against various forms of capital well-being, including financial, innovation and spiritual capital. If we apply Miller’s analysis to the IP industry as a whole, many (if not most) firms would fall into what Miller defines as the Administrator phase of their evolution, indicated with a blue dotted line in the chart below.

*Adapted from Barbarians to Bureaucrats: Corporate Life Cycle Strategies and Sustainable Wealth, by Lawrence M. Miller

According to Miller, organisations are in the Administrator phase when they no longer respond to the challenges of the external environment but seek instead to use internal solutions and protections as a means of innovation. The world around the Administrator may be undergoing rapid change, but their response is to turn inwards and protect what feels secure. Some of the characteristics he uses to describe this phase include;

Miller notes that organisations in the Administrator phase are often at their most wealthy during this period, especially in financial terms (see graph below). He states, “During this period the financial assets are growing, brand equity is increased, and human capital is increasing with the capacity to produce. It is likely that spiritual capital is the first resource that will decline during this period, followed by the loss of innovation and then internal sociability and trust. These losses are the leading indicators of decline”.

Most IPSB leaders that I speak to recognise that substantial changes to their external environment are now taking place. However, when we look at their responses we see mostly operational and management improvements and growth strategies focused on horizontal expansion through mergers and lateral hires. Continuing to sell known services to an enlarged client pool is the default strategy for many firms. This is not surprising, IPSB’s have benefited from enormous growth in the IP system over the last twenty years that has been both a boon and a barrier to innovation. This extraordinary expansion of the IP system has come as a result of a number of external factors, including:

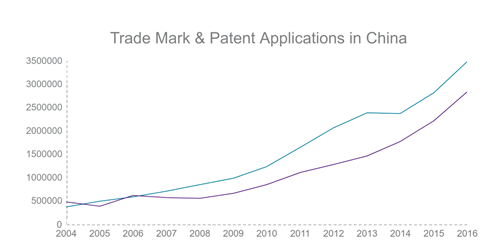

Trade Mark & Patent Applications in China from 2004 – 2016, source: SIPO website

New Accepted First-instance Civil Litigations from 2005 – 2016, source: SIPO website

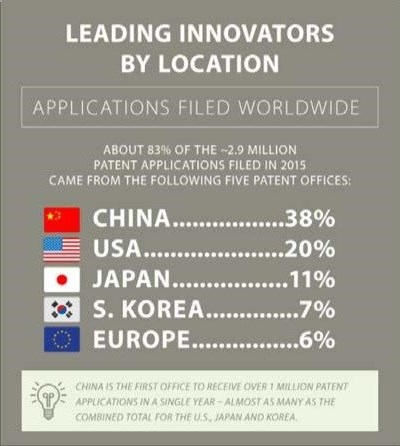

Source of image: www.morningsideip.com/global-patent-trends-according-to-wipo/

These external factors have contributed in large part to the growth in demand for IP services around the world. This has manifested in many jurisdictions, especially China, in the form of IP asset bubbles and IP thickets (see IP registration and activity graphs below). The effect of this on ISPB’s has been to push them into a highly reactive mode of growth where the focus is on servicing demand and ensuring outcomes are delivered at the right cost. Over the long term, this mode of growth leads to systemic risks as ingrained and reactive reactive behaviours result in an increasing unwillingness to invest in new service innovations. Viewed through this lens, it is easy to see the familiar protective pattern of Miller’s Administrator.

Miller argues that a long term trajectory that brings about growth in the five forms of well-being can be achieved by the Synergist. However, this can only occur when;

“Transformation is brought about by leaders who recognise new challenges, acknowledge the failure to adapt to a changing landscape, and promote a new outlook, a new spirit, and new strategy”

It is leadership of this kind that IPSB’s need now if they are to transform their services in line with their external environment. Failure to do so will only accelerate the potential for disruption to come from outside the IP system, a reality that has decimated other change resistant industries in the last decade. At present this disruption feels remote to most IPSB’s while the pressure for change remains distant. In part this is because the financial stocks of the Administrator are high and clients continue to demand the services they offer. As mentioned earlier, IPSB’s are also protected by industry barriers that make external disruption challenging, barriers that are reducing fast as harmonisation, deregulation and globalisation gain greater traction.

The threat of external disruptions

Online marketplaces are seeking to build and integrate critical support services in an attempt to reduce transaction costs and drive new business to their market. It stands to reason that this will soon encroach on the commoditised end of IP services, such as the filing, registration and online protection of IP rights. Alibaba is a front runner, at least on the finance and payments side, but can it overcome a critical credibility gap in relation to IP services? Could it realistically integrate a broader suite of IP services? Many will argue that it cannot, that the scale and reputation for IP infringement in China is too much of a barrier for a Chinese based marketplace to overcome. However, the strength of Jack Ma’s international ambitions are underpinned by an intellectual property imperative and so this could drive Alibaba faster towards developing an online IP services solution to attract new international customers. Another factor to consider is the advantage that China now provides as a platform for disruption, for example:

However, there are many potential sources of external disruption aside from online marketplaces. Auction houses, payment providers, accountancies, insurance companies and technologies like Blockchain are just some of the businesses outside the IP industry threatening the services that IPSB’s provide. How quickly they gain traction with IP owners and disintermediate the services ecosystem depends on how quickly IPSB leaders respond.

WHAT MIGHT IPSB INNOVATION LOOK LIKE?

At a strategic level, I believe there are five critical questions that IPSB’s must ask:

1. What is the mindset of their organisation? – Is the mindset defensive and closed? Is it seeking to limit and narrow the view of IP? Or does it encourage a broad and expansive perspective? There are various ways to gauge this, including by reference to the stories that people tell within the organization and the language that is used. Are narratives generally critical and dismissive of competitors that are innovating and seeking new ways to serve clients, or enquiring and curious? Another way to assess mindset is to look at the skills and capabilities that are being developed as well as the willingness of people with different skills and experiences to collaborate. The solutions of the future will come from the ability of IPSB’s to integrate, connect and apply the skills of a diverse network and building the organizational mindset to support this is the first key task of its leaders.

2. An IP activity and/or value focus? - as the cost of capital increases and growth slows, investment patterns will change. Companies will come under increasing pressure to explain the value of the IP they invest in, resulting in either a rapid decline in the volume of IP activity they instruct, or a gradual rebalancing. In this environment IPSB’s dependent on IP activity will need to find new paths to growth. Building new service lines and expanding into new markets requires time, new expertise and considerable investment, things that most IPSB’s do not have. The default solution is therefore to merge and build scale in IP activity. We are already seeing this in many developed markets, but particularly Australia where growth has flat-lined and the deregulation of the industry has accelerated the ability of the market to consolidate.

IPSB leaders who seek to innovate away from an activity focus and up the value chain will face numerous challenges. Firstly, the nature of the client conversation changes. It becomes more important to understand what is valuable to the client and to speak their language than it does to be expert in a given field. Consequently, leaders discover very quickly the challenge of developing and differentiating skills and capabilities. Some IP professionals excel at being subject matter experts and thrive on showcasing their expertise to the world. Others can take the conversation to higher levels of abstraction, where problems are unknown. In this realm subject matter expertise can be a barrier to clients getting the value they seek. Learning how to differentiate, develop and focus these capabilities in the right way is an important challenge facing IPSB leaders.

3. Is the organisation a truly diverse and connected one? - How to create an environment that is able to effectively ‘connect diversity’? What do these words mean in the context of your organisation? At Rouse this has meant asking ourselves three simple questions:

An example of how we have tried to put these questions into action is the decision we recently took to promote 25 new Executives to become members of Rouse LLP. In our language becoming an Executive is equivalent in many respect to becoming a partner in a law firm. An Executive at Rouse is a person that has a stake in the overall business and who feels connected and responsible for the business as a whole. Traditionally we have always viewed an Executive in the same narrow way that a law firm would, with the same tests and expectations of partnership. Becoming a member of the Rouse LLP for the last fifteen years has been a process that would look much the same in any multinational law firm. However, we realised that this approach is not fit for our future and required radical overhaul. Our new approach aims to open up membership to a much more diverse group. We promoted non-fee earners and fee earners alike, and ensured these people came from the most diverse backgrounds. We also gave them all stakes in the holding entity ensuring that everyone feels a sense of connection to the whole.

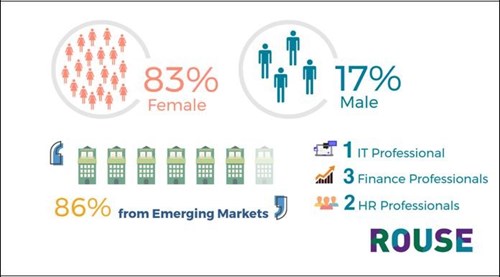

The full extent and nature of these Executive promotions are best demonstrated in the visuals below.

Note: Rouse promoted 24 new equity executives following the firm’s strong performance in the financial year to April 2017 including Moscow, Dubai, Bangkok, Jakarta, Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, London and Hanoi.

Note: The new cohort of executives has been drawn from across a wide range of different business functions, including professionals from the company’s IT, finance and HR disciplines, in addition to fee-earners.

4. What are the new business models you can learn from? - To compete over the long term, IPSB’s must be open to alternative models that enable them to innovate more freely and operate in faster and more flexible ways. This will lead more quickly to innovations in services, pricing, recruitment, training and development, marketing and application of technology. It will also attract new types of clients who see their IP needs being met in ways that narrowly defined business models cannot. New models are emerging, on the back of changes such as deregulation, Blockchain, mobilization of flexible working through the Internet, outsourcing and in-sourcing, and crowd-sourcing. Instead of protecting and defending old models like an Administrator, leaders must celebrate and learn from these new innovations. They are shaping our industry whether we like it or not and our leadership challenge is to ensure we learn from them.

Innovation at Rouse: What are we doing to lead change?

Rouse is an IP firm that for twenty years has focused on delivering clients quality IP outcomes in the challenging markets of China, South East Asia, the Middle East and Russia. We are a classic example of a business that has had to react to the massive explosion in demand for IP activity and our business model has, for the most part, remained the same, that of a traditional international IP firm. Our clients come to us because we offer international standard services and reliable outcomes in markets where this is not easily achieved. Much like our competitors, our development has been a reactive story, growing more and more of the same services in response to continued client demand and expanding these services horizontally as we search for growth. For all this time we have benchmarked ourselves against other law firms, maintaining a narrow mindset focused on containing IP within defined legal activities and outcomes.

Our leadership team came together in 2015 and quickly recognized the Administrator within us. While we felt that client demand for our services remained high, we could see that the external environment was changing far faster than us. Furthermore, although our financial performance had never been stronger, we could sense that the non-financial forms of well-being were in decline, particularly innovation. As a result we put in place a strategic plan at the beginning of 2016 that has had a transformative impact on the areas of well-being that we sought to improve. This strategy was built around four objectives:

1. A transformation of mindset

Across the organisation we aim to think, talk and behave as if we are a much broader IP church, with an open and diverse mindset. IP is no longer viewed narrowly as something that only qualified attorneys do, but as an asset that everyone in our network has a role in helping to create and add value to. We want this to be the experience that clients have when they interact with Rouse, whoever that person might be. This mindset starts at the top. As CEO it has been my number one priority to help reinforce the right narrative both internally and externally, and I can hear this coming through now in the conversations that are happening at all levels of the company.

2. IP consultancy as the key to unlocking value

We believe that IP consultancy holds the key to unlocking questions of value and not just in relation to traditional forms of IP (e.g. patents, designs, copyright and trade marks) but in the broader sense of intangible assets. Through a consulting approach we have found more appropriate tools and processes (both internally and through collaborations) that enable us to unlock more value for clients. This is especially relevant as clients seek to identify and extract value from new and emerging forms of IP asset, such as algorithms, e-secrets and social commerce.

To develop the skills and capabilities needed for consultancy requires a separate focus. Consultancy will not grow if ‘housed’ in an environment that is focused on the delivery of legal expertise and IP activity. Reorganising the way we are structured in Rouse to facilitate this focus has been a critical step. As a result, our UK business will now focus 100% on spearheading the development of our IP consulting services and will no longer provide downstream legal activity services. This is an exciting time for the UK and for the firm as a whole. Our London office is returning to its roots in many respects, operating as an innovation hub for the business, developing strategic consultancy relationships and engagements that benefit the whole of Rouse.

IP consultancy + IP activity

To some extent consultants must be removed from downstream activity. A degree of objectivity is required if consultants are to question the value of certain activities. However, that cannot be at the expense of connectivity and speed. Often clients will want consultants to help manage the implementation of a strategy or solution, especially in emerging markets where implementation brings its own challenges and risk. At other times consultants will be asked to pass over the implementation to specialist lawyers, or accountants, or trade mark attorneys etc. The critical point is ensuring that the organisation is optimised to allow consultancy + implementation of activity to happen in the most connected and time-effective way possible. There needs to be a degree of separation, whilst retaining the ability to implement quickly and effectively if required.

3. Three differentiated but integrated business models

We see three different IP service models required to deliver on the innovation needs of our clients. As noted above, our challenge is to ensure that each model has the right independent focus but at the same time is integrated and connected in such a way that clients do not lose the advantage of speed and connectivity. If these models operate in silos or are too removed from each other, then clients lose that advantage.

The three models are:

a) Consultancy– built around IP tools and processes and applied by a small and diverse team of consultants. This model is built upon analysis, benchmarking and insight being carried out up front and often before any fees are incurred. In this sense the model is front loaded and requires a long lead time to reach profitability.

b) Legal– built on a network of lawyers with deep expertise in a given practice. This model is well known and based largely around time based fees. In many countries law firms are regulated and so there is the added complexity of ensuring these services are delivered properly and transparently through an independent law firm structure. We do this through a network approach ensuring that law firms within the Rouse network get seamless access to the consultancy services that they and their clients need (and vice versa).

c) Portfolio & enforcement (including online enforcement) – built around technology and process capability combined with the right level of people expertise. This is largely a fixed fee based model and requires sufficient scale to ensure that gains made from technology and process improvements can be passed on to clients.

Each one of these service models delivered on their own is not that novel. There are good law firms providing IP legal services, some good consultancies doing IP work and a number of good portfolio companies providing multi-country filing and prosecution services (probably the area that has seen the most innovation and aggregation). However, very few have been able to develop and integrate these three service models successfully across an emerging markets network, and with a developed market leading in IP consultancy.

4. Connecting diversity

I mentioned above the steps that we are taking to build the most diverse Executive leadership team possible. However, below that we are actively recruiting, developing and promoting different people from more diverse backgrounds than before. We recently hired a finance consultant into a practice team to help them better understand the financial impact of certain IP activities on the clients business. We have hired into our consultancy technology specialists, science & innovation policy experts and project managers all with a view to expanding our understanding of IP value. This diversity of recruitment would not have been supported or encouraged under our old ‘law firm’ mindset.

As previously mentioned, it is just as important to connect this diversity to itself and to the organization if it is to create a real advantage. Rouse has always had a relatively horizontal structure but as we bring in and develop a more diverse group of leaders there is then greater emphasis on the need to promote and support collaboration and connectedness. We do that by reinforcing three things. Firstly, by reinforcing the right culture and behavior in the way that we reward and incentivize people. Secondly, by making sure that our structure does not get too vertical and that people are always encouraged to speak to and connect with whomever they need, no matter how senior. And thirdly, by investing in communication technology that allows people to connect effectively across offices.

Conclusion

The IP industry is in need of transformation if it is to keep pace with its external environment. Recognising this failure to adapt is the first challenge of its leaders. This paper contains more questions than it does answers but transformation starts by asking the right questions. Whether the organization’s mindset is prepared for the future and what the impact of prolonged reactive growth is on innovation capacity is a good place to start. Another good question is understanding what is valuable IP as opposed to what is simply an IP activity done well. However, ultimately if IP leaders are to find a path to sustained growth and well-being, they must be prepared to promote and connect diversity, respecting the innovation that is happening around them rather than engaging in the critical behaviours of the Bureaucrat.